The Temple Grandin of Shadow Banking

A most excellent set of missives from Jeffrey P. Snider regarding structural liquidity limitations in the SBS - Shadow Banking System. As usual, in the end we shall muse.

Excerpts from Attending The Exits: Low interest rates "forced" participants into new means and measures for creating returns. In some cases, insurance companies and other large institutions that had large stores of largely inert bond positions, including a "wealth" of UST and MBS, began to run large securities lending operations to generate an additional spread. Enhancing that further meant lending a single security in more than one instance, sometimes over and over and over.

A further complication arose as dealers began to participate on both sides, borrowing repo to fund balance sheet positions while also lending out securities in their warehouse inventory - all designed to reduce borrowing costs as close to nothing as possible while at the same time picking up as many basis points of return as humanly possible.

The problem is that credit securities are not always "available" for market needs. It seems as if balance sheet costs for holding market-available inventory now far outweigh any spread that might be picked up for doing so. That is saying something given that negative repo rates have become, apparently, far more frequent and deeper.

The less credit securities are in this "ready" position, the greater the problem with respect to acute outbursts of demand (either for a particular security or for repo in general). What we are really talking about here, in big picture terms, is the size of the exit. In all honesty, for all the endless talk about liquidity, what it really represents is the ability to take on a significant and determined selling pressure without courting major disruption and disorder.

The size of the exit has grown significantly smaller just in the past year or so (probably since QE3 started its disruptions), after having already done so consistently since 2007.

But that is actually worse than it sounds. While the exits have grown narrower and flimsier, the actual size of holdings that someday might be in serious need of exits has grown massively at the same time.

It is now well-beyond just corporate debt and dealer capacity to handle potential disorder in that narrow circumstance. That has been echoed and replicated under real, but relatively calm conditions, in MBS and now UST repo. Everywhere you look in credit "liquidity" there is a diminished feel. That is not good. Very narrow doors and huge and growing crowds (all on the same side) is an unnecessary risk.

Excerpts from Attending The Exits Part 2

In the earlier days of the euro, European banks remained dollar steady, opening up a short dollar position of biblical proportions (that we still have little idea of how large it was), and were the largest source of credit production for the mania portion of the housing bubble. From Spain and Germany to the UK and Switzerland, global banks were financializing the US through eurodollar "liquidity."

Japanese banks have been consistently the second largest dollar "short" in the world; dollar swaps between the Fed and other central banks usually place Japan second in usage.

In 2011, Concerns about the tiny Greek financial economy, opened a hole in the dollar flow system largely because so many of those European banks were also dollar asset holders and users of eurodollar liquidity. Dollar liquidity and thus asset prices were imperiled as the European dollar "bid" (or short) was threatened by very European problems.

That harrowed narrowing of the exits is usually a private affair, with central banks stepping in long after the carnage has been assumed. Most people, including probably every single casual observer, notice such dysfunction and disorder solely by proxy of stock prices. But in the middle of 2013, dollar chaos manifested in ways and manners far more remote than that slender focus.

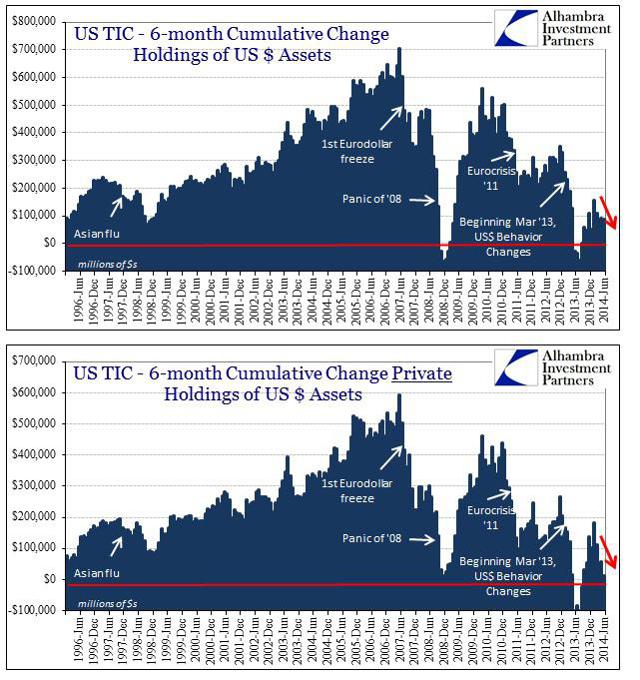

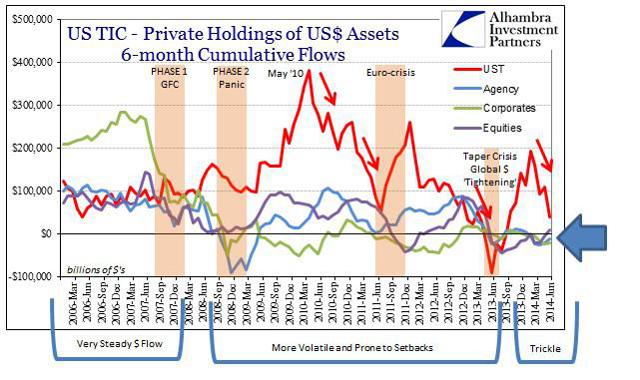

If you observe the cumulative action of the private financial system, you can see just how much of a mess these four instances (2 phases of the GFC, euro crisis, and taper selloff) have created in US$ flow. The reduction in holding of US$ assets takes place because of liquidity problems, and thus the congregation of them into singular waves is the visible aftermath of exactly that disorder. However, where stock prices were noticeably impacted in 2007, 2008 and even 2011, there was little notice of the grand disruption in 2013 - unless you paid attention to eurodollars, MBS (in particular) and foreign currencies (pretty much the rest of the world).

A longer-term view shows just how diminished the US$ bid (perpetual short) has become after repeated dollar episodes - all dating back to August 9, 2007.

This interrupted dollar stream is the financial equivalent of narrowing the exits. This is in addition to internal systemic pressures I tried to describe of the repo markets. You have internal systems that are far less robust than they were even in 2008, and now on top of that there is a much smaller external financial bid as financial confidence in the US$ wanes dramatically.

The rift in the global eurodollar exchange system that opened in 2007 is not closing, rather it remains in a state of paradigm shift that can only strain further a liquidity system that has actually lost robustness from even its weakened state just prior to near-collapse.

Nattering Note: As for explaining the dollar shorts, this piece is well put, no pun intended.

Excerpts from Attending The Exits Part 3

When speaking of "inflation", another overly generic allusion, the economist undoubtedly refers to increasing the "money supply" in order to achieve it as if one follows directly from the other.

That is a problem not just in understanding the concept of price changes, but also basic systemic function and liquidity. One hundred billion dollars in the hands of an insurance company is not the same as $100 billion in a ledger of an ABS issuer in 2004. What counts in not the count, but moving deeper into motivations and flexible designs.

Where and how "money" arrives and in whose hands it ultimately resides is far, far more important than how much exists.The fragmentation that nearly ruined all of it beginning in 2007 was about exactly this problem - that singular and generic notions of money supply were completely unimportant; instead it was about flow, or how "dollars" go from A to B and then C and D.

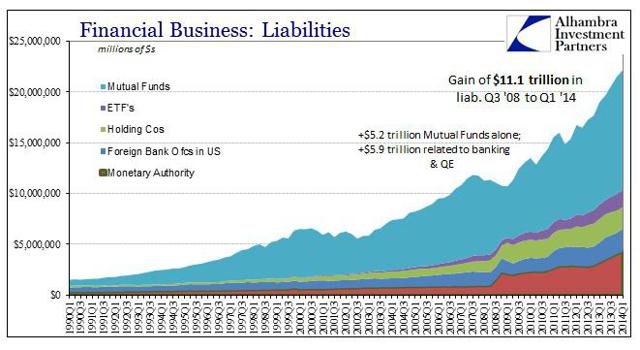

The buildup of liabilities in ETFs and Mutual Funds amounts to a significant reorientation of financialism, especially as it relates to liquidity and the scale of potential exits.

Part of this can be seen by what is not shown in either group above - depository institutions, insurance companies and pension funds. These are the backbone of the financial system, offering more than just a repository for assets. These are among the most flexible of the potential vehicles to contain liabilities, particularly as it relates to crowded trades becoming overturned (the herd turning).

With that in mind, there is more than a trivial distinction with liabilities carried in a bank versus that carried in a mutual fund. In the former, if you and enough people like you remove your claims on the vehicle (likely a deposit amount) the bank has recourse to other sources of funding before having to resort to asset sales of increasing intensity.

Again, 2007-08 showed that can be very problematic, particularly when internal systems are not aligned or even functioning, but the flexibility of the design at least permits such absorption. The bank can raise funds in the repo market or the Discount Window, even sell debt and raise equity capital, even pension funds and insurance companies as alternates have a variety liquidity options before appealing to the dark side of fire sales.

Transferring that claim from a bank as a vehicle to hold assets to a mutual fund removes all flexibility. A rush of withdrawals on mutual funds can only end with asset sales, unless the funds are holding enough cash on hand, which we know is not the case currently with cash balances at record lows. In the case of the crowded trade, there will be no option but asset sales.

This as true in credit as stocks, particularly since mutual funds have added a staggering $2.25 trillion in credit instruments since ($1.1 trillion in corporate bonds alone) to go with an additional $4 trillion in stocks at current prices.

That translates to potential liquidity "gating", or narrow exits - the simple lack of capacity to absorb rapid changes or inflections.

More to come in Part 2.

Excerpts from Attending The Exits: Low interest rates "forced" participants into new means and measures for creating returns. In some cases, insurance companies and other large institutions that had large stores of largely inert bond positions, including a "wealth" of UST and MBS, began to run large securities lending operations to generate an additional spread. Enhancing that further meant lending a single security in more than one instance, sometimes over and over and over.

A further complication arose as dealers began to participate on both sides, borrowing repo to fund balance sheet positions while also lending out securities in their warehouse inventory - all designed to reduce borrowing costs as close to nothing as possible while at the same time picking up as many basis points of return as humanly possible.

The problem is that credit securities are not always "available" for market needs. It seems as if balance sheet costs for holding market-available inventory now far outweigh any spread that might be picked up for doing so. That is saying something given that negative repo rates have become, apparently, far more frequent and deeper.

The less credit securities are in this "ready" position, the greater the problem with respect to acute outbursts of demand (either for a particular security or for repo in general). What we are really talking about here, in big picture terms, is the size of the exit. In all honesty, for all the endless talk about liquidity, what it really represents is the ability to take on a significant and determined selling pressure without courting major disruption and disorder.

The size of the exit has grown significantly smaller just in the past year or so (probably since QE3 started its disruptions), after having already done so consistently since 2007.

But that is actually worse than it sounds. While the exits have grown narrower and flimsier, the actual size of holdings that someday might be in serious need of exits has grown massively at the same time.

It is now well-beyond just corporate debt and dealer capacity to handle potential disorder in that narrow circumstance. That has been echoed and replicated under real, but relatively calm conditions, in MBS and now UST repo. Everywhere you look in credit "liquidity" there is a diminished feel. That is not good. Very narrow doors and huge and growing crowds (all on the same side) is an unnecessary risk.

Excerpts from Attending The Exits Part 2

In the earlier days of the euro, European banks remained dollar steady, opening up a short dollar position of biblical proportions (that we still have little idea of how large it was), and were the largest source of credit production for the mania portion of the housing bubble. From Spain and Germany to the UK and Switzerland, global banks were financializing the US through eurodollar "liquidity."

Japanese banks have been consistently the second largest dollar "short" in the world; dollar swaps between the Fed and other central banks usually place Japan second in usage.

In 2011, Concerns about the tiny Greek financial economy, opened a hole in the dollar flow system largely because so many of those European banks were also dollar asset holders and users of eurodollar liquidity. Dollar liquidity and thus asset prices were imperiled as the European dollar "bid" (or short) was threatened by very European problems.

That harrowed narrowing of the exits is usually a private affair, with central banks stepping in long after the carnage has been assumed. Most people, including probably every single casual observer, notice such dysfunction and disorder solely by proxy of stock prices. But in the middle of 2013, dollar chaos manifested in ways and manners far more remote than that slender focus.

If you observe the cumulative action of the private financial system, you can see just how much of a mess these four instances (2 phases of the GFC, euro crisis, and taper selloff) have created in US$ flow. The reduction in holding of US$ assets takes place because of liquidity problems, and thus the congregation of them into singular waves is the visible aftermath of exactly that disorder. However, where stock prices were noticeably impacted in 2007, 2008 and even 2011, there was little notice of the grand disruption in 2013 - unless you paid attention to eurodollars, MBS (in particular) and foreign currencies (pretty much the rest of the world).

A longer-term view shows just how diminished the US$ bid (perpetual short) has become after repeated dollar episodes - all dating back to August 9, 2007.

This interrupted dollar stream is the financial equivalent of narrowing the exits. This is in addition to internal systemic pressures I tried to describe of the repo markets. You have internal systems that are far less robust than they were even in 2008, and now on top of that there is a much smaller external financial bid as financial confidence in the US$ wanes dramatically.

The rift in the global eurodollar exchange system that opened in 2007 is not closing, rather it remains in a state of paradigm shift that can only strain further a liquidity system that has actually lost robustness from even its weakened state just prior to near-collapse.

Nattering Note: As for explaining the dollar shorts, this piece is well put, no pun intended.

Excerpts from Attending The Exits Part 3

When speaking of "inflation", another overly generic allusion, the economist undoubtedly refers to increasing the "money supply" in order to achieve it as if one follows directly from the other.

That is a problem not just in understanding the concept of price changes, but also basic systemic function and liquidity. One hundred billion dollars in the hands of an insurance company is not the same as $100 billion in a ledger of an ABS issuer in 2004. What counts in not the count, but moving deeper into motivations and flexible designs.

Where and how "money" arrives and in whose hands it ultimately resides is far, far more important than how much exists.The fragmentation that nearly ruined all of it beginning in 2007 was about exactly this problem - that singular and generic notions of money supply were completely unimportant; instead it was about flow, or how "dollars" go from A to B and then C and D.

The buildup of liabilities in ETFs and Mutual Funds amounts to a significant reorientation of financialism, especially as it relates to liquidity and the scale of potential exits.

Part of this can be seen by what is not shown in either group above - depository institutions, insurance companies and pension funds. These are the backbone of the financial system, offering more than just a repository for assets. These are among the most flexible of the potential vehicles to contain liabilities, particularly as it relates to crowded trades becoming overturned (the herd turning).

With that in mind, there is more than a trivial distinction with liabilities carried in a bank versus that carried in a mutual fund. In the former, if you and enough people like you remove your claims on the vehicle (likely a deposit amount) the bank has recourse to other sources of funding before having to resort to asset sales of increasing intensity.

Again, 2007-08 showed that can be very problematic, particularly when internal systems are not aligned or even functioning, but the flexibility of the design at least permits such absorption. The bank can raise funds in the repo market or the Discount Window, even sell debt and raise equity capital, even pension funds and insurance companies as alternates have a variety liquidity options before appealing to the dark side of fire sales.

Transferring that claim from a bank as a vehicle to hold assets to a mutual fund removes all flexibility. A rush of withdrawals on mutual funds can only end with asset sales, unless the funds are holding enough cash on hand, which we know is not the case currently with cash balances at record lows. In the case of the crowded trade, there will be no option but asset sales.

This as true in credit as stocks, particularly since mutual funds have added a staggering $2.25 trillion in credit instruments since ($1.1 trillion in corporate bonds alone) to go with an additional $4 trillion in stocks at current prices.

That translates to potential liquidity "gating", or narrow exits - the simple lack of capacity to absorb rapid changes or inflections.

More to come in Part 2.

Comments